Summary

A Johns Hopkins study revealed that symptoms related to dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system, including Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), can occur in patients with Post-Treatment Lyme Disease (PTLD). Researchers also identified a subgroup of PTLD patients who experienced orthostatic tachycardia, a condition where the heart rate rises abnormally fast when moving from lying down or sitting to standing. This rapid heartbeat can cause symptoms such as dizziness, lightheadedness, and fatigue, that are often present in PTLD.

Why was this study done?

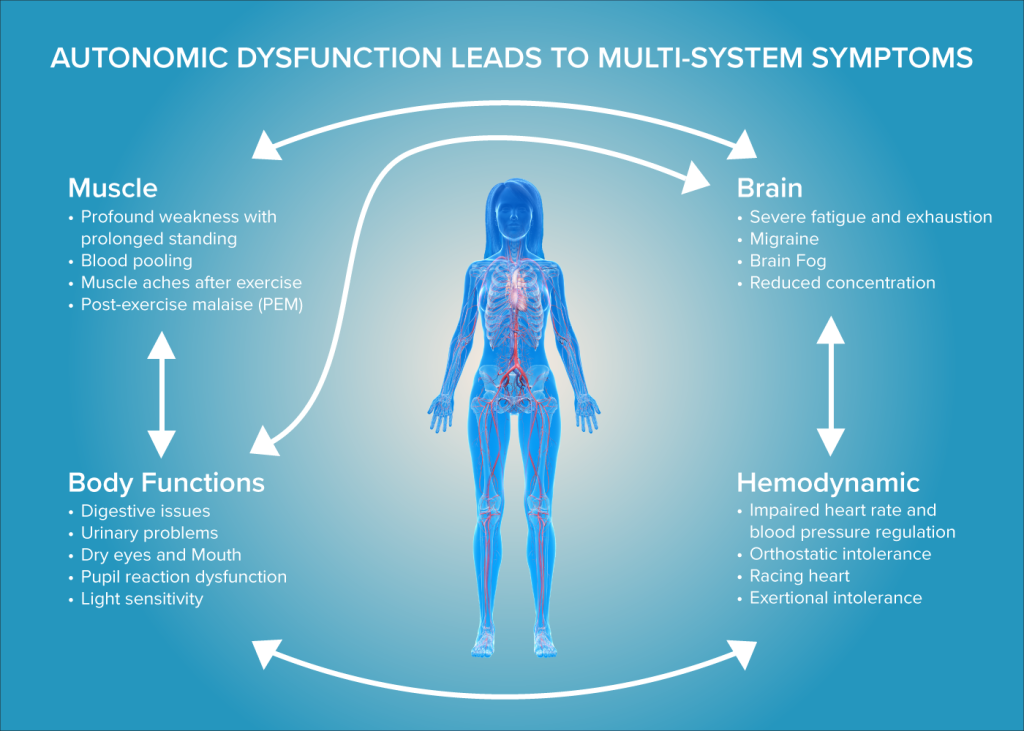

Patients with Post-treatment Lyme Disease (PTLD) often suffer prolonged symptoms such as severe fatigue, pain, and cognitive difficulties, but the role of autonomic nervous system dysfunction is not fully understood. POTS is an autonomic disorder characterized by rapid heartbeat and symptoms like dizziness and brain fog upon standing, and it has been reported after Lyme disease. Symptoms overlap with conditions like Long COVID, where autonomic dysfunction is common. This study systematically evaluated autonomic symptoms and changes in blood pressure and heart rate in PTLD.

How was this study done?

Johns Hopkins researchers studied two groups of confirmed Lyme disease patients with persistent symptoms. One cohort of 37 PTLD patients completed the COMPASS-31 autonomic symptom questionnaire and was compared to POTS patients and healthy controls. A larger group of 210 PTLD patients underwent a clinical 10-minute active stand test measuring heart rate and blood pressure changes upon standing upright, compared with healthy controls.

What were the major findings?

Using the COMPASS-31 symptom survey and a 10-minute active stand test, results showed the PTLD patients had significantly higher autonomic symptom scores than healthy controls, with symptom profiles similar to POTS patients, including orthostatic intolerance, vasomotor, and bladder dysfunction. A subset of about 4.3% of PTLD patients exhibited orthostatic tachycardia, defined as a sustained heart rate increase of at least 30 beats per minute during a stand test, a hallmark of POTS and marker of autonomic dysfunction.

Those with orthostatic tachycardia were more likely to be earlier in their disease course and more likely to have received steroids and antibiotics. Blood pressure drops (orthostatic hypotension) were common but not significantly different from controls. Importantly, many POTS symptoms like fatigue, brain fog, heart palpitations, and dizziness were found to overlap with PTLD symptoms.

What is the impact of this work?

This study shows that autonomic symptoms, including lightheadedness, gastrointestinal problems, and bladder symptoms, are very common in post-treatment Lyme disease (PTLD). We also found that a small subgroup of patients develops an abnormal heart rate increase when standing, known as orthostatic tachycardia, and that this group tends to experience more severe symptoms.

These findings suggest that problems with the autonomic nervous system may contribute to ongoing symptoms in some people with PTLD, highlighting the importance of routinely assessing autonomic symptoms in clinical care. Simple screening tools like the COMPASS-31 questionnaire and the 10-minute active stand test can help identify possible autonomic involvement. More specialized testing, such as a tilt table test, can be considered if autonomic dysfunction is suspected and initial screening is inconclusive.

Timely diagnosis can lead to more targeted and effective treatments, including lifestyle modifications, blood volume expansion, or appropriate medications, that have the potential to improve symptoms and substantially improve patients’ quality of life. By fostering earlier recognition and comprehensive care, these autonomic evaluations provide a critical step toward breaking the cycle of chronic symptoms and advancing meaningful recovery for those affected by Lyme disease related autonomic dysfunction.

This study offers renewed hope that with growing awareness, better tools, and focused care, patients living with Lyme disease associated autonomic symptoms can move closer to lasting relief and restored well-being.

Study team members:

Brittany L. Adler, MD1*; Alison W Rebman, MPH1*; Tae Chung, MD2; John B. Miller, MD1; Marzieh Keshtkarjahromi, MD, MPH3; Ting Yang, PhD1; Chatuthanai Savigamin, MD, MSc, MPH1; Alba Azola, MD2,4; Peter C. Rowe, MD4; John N Aucott, MD1

*These authors contributed equally to this work

- Lyme Disease Research Center, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD

- Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD

- Department of Medicine, Sibley Memorial Hospital, Johns Hopkins Community Physicians, Washington, DC

- Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD

This research was supported by:

Global Lyme Alliance (BA)

National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) K23AI180356 (BA)

Steven and Alexandra Cohen Foundation (JA, AR)