Summary

Using advanced MRI brain scans, Johns Hopkins researchers led by Cherie Marvel, PhD, uncovered unexpected patterns of white matter activity in people recovering from Lyme disease. Notably, during early infection, robust white matter signals predicted a higher likelihood of full recovery. These findings suggest that restorative, rather than degenerative, white matter activations are associated with better patient outcomes.

Why was this study done?

After antibiotic treatment for Lyme disease, 10–20% of patients experience prolonged symptoms such as fatigue, pain, and cognitive difficulties, a condition known as Post-Treatment Lyme Disease (PTLD). This study sought to understand how Lyme disease affects the brain from early infection through recovery, and whether brain imaging markers could help identify biological risk and resilience factors early on to better inform treatment approaches and improve patient outcomes.

How was this study done?

Dr. Marvel’s team used advanced brain imaging, including functional MRI (fMRI), to measure brain activity in patients who recovered fully, compared to those who developed PTLD, and healthy controls. Participants were followed over time with repeat brain scans and clinical evaluations to track changes in brain activity, symptoms, and functioning.

What were the major findings?

Unexpectedly, patients recovering from Lyme disease showed increased white matter activity, a pattern not typically seen in infectious conditions. Stronger white matter signals correlated with better cognitive performance, improved mood, and fewer overall symptoms.

What is the impact of this work?

This study reveals that heightened white matter activity early in Lyme disease may be a positive sign, marking patients who are more likely to return to health after infection and treatment. In contrast, patients who lack this early brain response appear more prone to developing Post-Treatment Lyme Disease (PTLD), highlighting a critical window when interventions may be most effective.

Because white matter is not typically highly active on functional MRI, its early engagement suggests the brain may be mounting an adaptive repair response. This research lays the groundwork for improved tools to identify high‑risk patients sooner and to guide treatment strategies that support brain repair and help reduce persistent symptoms.

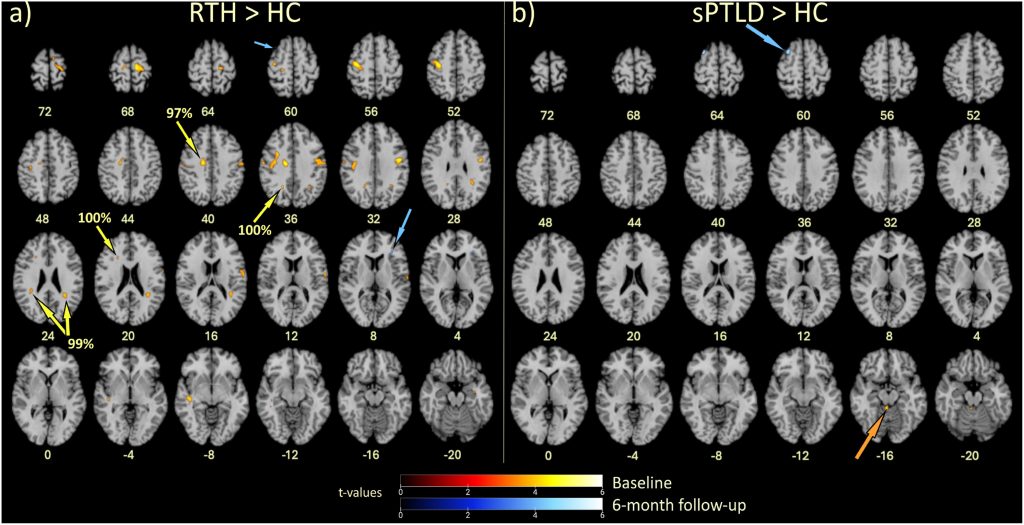

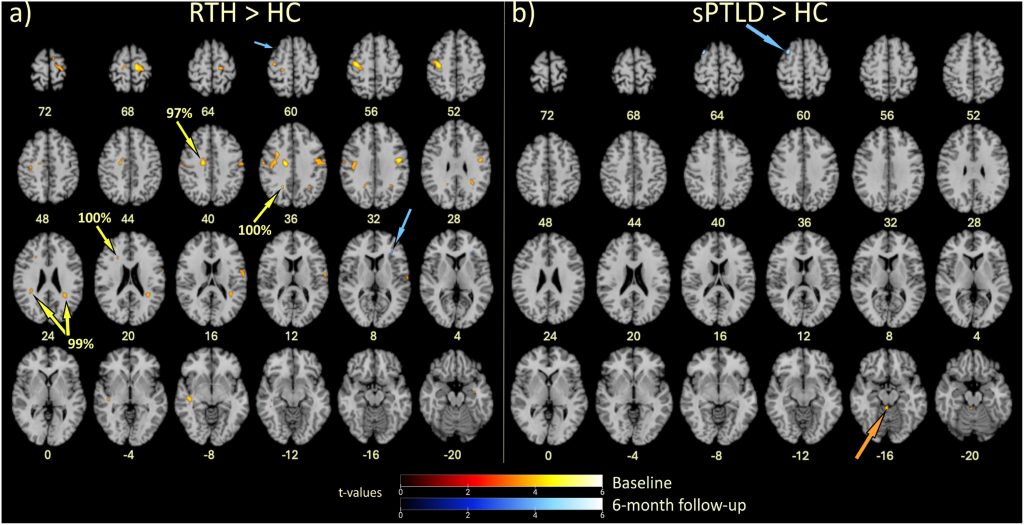

(a) People with Lyme disease who later returned to health (RTH) showed elevated brain activity soon after infection, relative to healthy controls (HC), shown highlighted in yellow. Many of these higher activations were located in white matter, with yellow arrows pointing to areas composed of more than 90% white matter. Blue arrows show the only two elevated activations 6 months later, indicating that most of the early extra activity had normalized over time.

(b) People who later developed symptoms of post-treatment Lyme disease (sPTLD) did not show the same robust early activations (orange arrow) soon after infection relative to HC and showed only one small area of elevated activity (blue arrow) 6 months later.

Healthy controls showed no signs of elevated brain activity relative to either patient group (not shown), indicating that these changes were related to whether people recovered from a Lyme disease infection or developed persistent symptoms.

Study team members:

Cherie L. Marvel 1 2, Alison W. Rebman 3, Kylie H. Alm2, Pegah Touradji4 , Arnold Bakker 1 2, Prianca A. Nadkarni 1, Deeya Bhattacharya 1, Owen P. Morgan 1, Amy Mistri 1, Christopher C. Sandino 1, Jonathan A. Ecker 1, Erica A. Kozero 3, Arun Venkatesan 1, Abhay Moghekar 1, Ashar A. Keeys 1, John N. Aucott 3

1Department of Neurology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, 21205, United States of America

2Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, 21205, United States of America

3Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, Lyme Disease Research Center, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, 21205, United States of America

4Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, 21205, United States of America

This research was supported by:

P-Squared Philanthropies